Taxation, Incarceration, and the Evidence for Housing First: A Research-Based Analysis of Homelessness Policy in Florida

- Destiny Wiggins

- Jul 22, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Sep 2, 2025

Florida’s Homelessness Policy Crossroads

Florida is at a turning point in how it responds to homelessness, incarceration, and public spending. Even though national and state-level research strongly supports Housing First strategies, the state continues to channel funds into jails and carceral systems instead of addressing housing instability at its core. This article examines Florida’s current policy landscape through a nonpartisan, evidence-based lens using research, government reports, and financial data to compare the effectiveness of Housing First versus incarceration models.

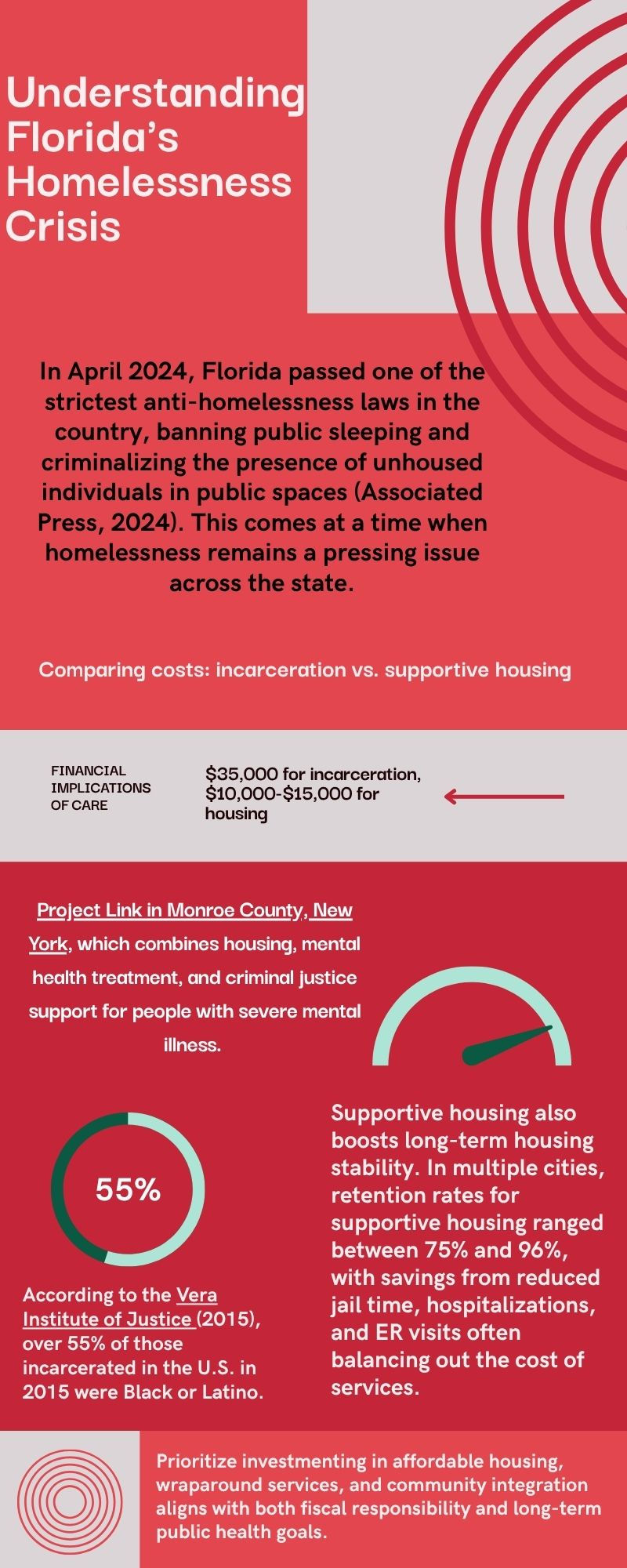

In April 2024, Florida passed one of the strictest anti-homelessness laws in the country, banning public sleeping and criminalizing the presence of unhoused individuals in public spaces (Spencer, Payne, (2024 2024). This comes at a time when homelessness remains a pressing issue across the state. According to the 2024 Florida Homelessness Count, around 32,000 people are unhoused on any given night, many concentrated in Central Florida (Council 2024).Service providers like The Sharing Center in Seminole County report operating at full capacity, often leaving people with no legal or safe place to sleep.

We Were Sleeping Behind a Grocery Store

For the past two years, Shonda Hawn has endured the devastating effects of homelessness. After losing her home while caring for her mother and then losing her job, she and her two children found themselves sleeping behind a grocery store in Sanford, FL.

“No one expect no children to be in an alley, with their eyes closed,” Shonda said.

The impact on her kids has been severe. They struggle with sleep and rarely eat full meals.

“You damage them because they're not stable,” she added. But things began to change when her friend Casey, whom she calls “an angel from God”; stepped in to help. Through

The Sharing Center, Shonda and her children were temporarily placed in a hotel, a small but meaningful step toward stability. Her future is still uncertain, but she’s holding onto hope.

“I will make it, I will. I have faith in me. I have faith once I do get established. I never let this happen again.”

Neil Waldron, another client of The Sharing Center, says the housing market feels impossible. He became unhoused after Hurricane Ian and says the new law only makes things worse.

“This law criminalizes people who are already struggling to survive,” said Keisha Thomas. “Many shelters, including the one in Seminole County, are full, and our center isn’t equipped to house individuals overnight.”

Thomas added that The Sharing Center helped over 900 families with food last month. “We feed those who are hungry, but we have no way to offer them shelter.”

Listen to Neil Waldron on SoundCloud

Stories like Shonda’s are far too common, and the numbers back it up. These types of policies increase displacement without addressing the root causes like access to affordable housing, mental health services, and poverty. Keisha Thomas, program manager at The Sharing Center, explained: "The ongoing enforcement of this law is pushing people into a cycle of displacement, making stable shelter and care harder to access."

Meanwhile, in 2000, Lee County debated a $38 million jail project. To avoid long-term debt, the county temporarily relied on commercial paper and cash reserves while asking voters to approve a one-cent sales tax (Whalen, 2000). Though dated, this example shows a trend: prioritizing incarceration over root-cause solutions to homelessness.

But there’s strong evidence that the Housing First model works better. Housing First offers immediate access to permanent housing without preconditions, followed by supportive services tailored to each person’s needs. According to the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH, 2019), this approach reduces the need for costly emergency services while improving overall health and housing stability.

One notable example is Project Link in Monroe County, New York, which combines housing, mental health treatment, and criminal justice support for people with severe mental illness. In one year, participants had 57% fewer jail days and 93% fewer hospital days (Lamberti, 2004). Similar outcomes have been found in other cities. In New York City’s FUSE II program, participants used shelters 70% less and spent 40% fewer days in jail than a control group (USICH, 2019). In Los Angeles, those in the Housing for Health program lowered public service costs by nearly 60% in just one year.

HUD’s Family Options Study also found that permanent housing subsidies led to better food security, school attendance, and mental health for both children and adults (Congressional Digest, 2020). Families also reported fewer incidents of domestic violence and family separation.

Emergency Housing for Justice-Involved Individuals: A Broader Look at National Trends

Recent experiments in California and New York illustrate how emergency housing strategies for justice-involved individuals can support both public health and long-term housing stability. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, California began leasing hotel rooms for people released from jail who lacked stable housing (VanSickle, 2020). Oakland alone secured 393 hotel rooms for this purpose. Sgt. Ray Kelly of the Alameda County Sheriff’s Office emphasized that the move was designed to "save lives," especially considering the dangers posed by COVID-19 in congregate living settings.

Similarly, New York City implemented hotel placements for individuals released from Rikers Island. These programs reflect a larger understanding that stable housing not only reduces recidivism but also promotes public health and community safety. Randall Kuhn, a public health professor at UCLA, noted these interventions provided a blueprint for how jurisdictions can support justice-involved individuals post-release, especially during times of crisis.

Stories like these support a growing body of evidence behind Housing First. The idea that people exiting incarceration face heightened risks of homelessness and must be prioritized for safe, supportive housing options. While hotel placements are not permanent solutions, they demonstrate that swift, coordinated, state-supported action can prevent homelessness and reduce strain on already overburdened emergency systems.

However, the urgency for more humane strategies becomes even clearer when examining the alternative: U.S. jails, many of which are plagued by overcrowding, neglect, and abuse. Investigations across California, New York, Texas, and Missouri have uncovered disturbing conditions, including detainees chained for days, unsanitary environments, lack of medical care, and severe staff shortages (Blakinger, 2022). In Los Angeles, some detainees reported being forced to relieve themselves on the floor due to broken toilets. Others have described jail conditions as even more dehumanizing than life on the streets.

These challenges are compounded by staffing issues in cities like Houston and Philadelphia, where chronic personnel shortages limit access to food, hygiene facilities, and even basic legal processes like court appearances. The consequences are deadly: deteriorating health, avoidable deaths, and severe trauma, especially for individuals with mental illnesses.

Despite brief reductions in incarceration during the pandemic, jail populations have risen again without the necessary resources to care for those detained. Meanwhile, prevailing narratives about homelessness continue to underestimate the scale of the crisis. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development's annual homelessness count only tracks individuals in shelters or visible public spaces on a single night (Foscarinis, 2014). This approach overlooks those who are couch surfing, temporarily hospitalized, or cycling through jails, all without permanent housing.

Maria Foscarinis of the National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty

argues that this undercount weakens policy responses by failing to recognize the full scope of homelessness. To her, real progress requires acknowledging housing as a human right and correcting the structural inequities that make stable housing inaccessible. She stresses the need for data that reflects hidden homelessness in order to guide meaningful change.

At the same time, the financial and social costs of incarceration are mounting. According to the Vera Institute of Justice (2015), over 55% of those incarcerated in the U.S. in 2015 were Black or Latino. In Florida, data from The Homeless Voice (2024) show Florida ranks second nationally in violent incidents targeting the unhoused, underscoring the physical dangers of policies that displace individuals without providing stable alternatives. Legislative decisions reminiscent of post-Civil War Black Codes disproportionately affect people of color and criminalize poverty rather than addressing its root causes (Florida Policy Institute, 2023). A growing consensus among policymakers, advocates, and researchers supports the systemic implementation of Housing First as a community-wide framework. This includes rapid re-housing, permanent subsidies, and supportive housing; all of which have shown long-term benefits in public safety, health outcomes, and fiscal sustainability.

In contrast, a wide coalition of policymakers, public health experts, and housing advocates now call for the systemic expansion of Housing First frameworks. This includes rapid re-housing, permanent subsidies, and long-term supportive housing, all of which have been shown to improve public safety, health outcomes, and cost efficiency. As Florida and other states face rising rates of homelessness and increasing pressure on carceral systems, the choice becomes clear: continue investing in handcuffs or build a pathway to housing, health, and stability for all.

Community Gaps and Grassroots Solutions

Chris Ham, director of Rescue Outreach Mission, stepped into leadership in 2021 when the shelter had only six employees. Since then, his team has grown to 25, and the shelter now houses up to 40 men, 28 women, and nearly 30 children in family units.

“Right now, we’ve got nearly 40 children on our waitlist,” Ham said. “We do everything we can, even offering emergency cots until we can find space.”

Affordable housing is the biggest barrier. Rent averages over $2,000 per month, and move-in costs often exceed $6,000.

“That’s just not realistic for most of the families we serve,” Ham said. “We need more affordable options and community support to make them happen.”

Rapid re-housing, which aligns with Housing First principles, has also proven effective. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs’ SSVF program placed 80% of participating veterans into permanent housing, even those with no income at entry. Monthly incomes rose from $251 to $450 on average. Compared to transitional housing, which costs over $32,000 per stay, rapid re-housing averages just $6,578.

Supportive housing also boosts long-term housing stability. In multiple cities, retention rates for supportive housing ranged between 75% and 96%, with savings from reduced jail time, hospitalizations, and ER visits often balancing out the cost of services.

Health Care on the Front Lines

Dr. Pia Vassorari, lead clinician at the Health Care Center for the Homeless, says older adults are increasingly at risk. Many of her patients have chronic illnesses that worsen due to stress, poor sleep, and exposure to the elements.

“They’re exhausted. They come in here and often fall asleep in the waiting room because it's the only safe space they’ve had in days,” Vassorari said.

She supports creative solutions like the proposed Dignity Bus, a mobile shelter that could give people a safe place to sleep, store medications, and begin recovery. “It gives people a place to pause, so they can focus on getting back on their feet.”

Conclusion

In conclusion, while counties like Lee explore funding mechanisms to expand incarceration capacity, and the state pursues punitive measures against the unhoused, research strongly supports a shift in priorities. Housing First approaches, supported by empirical data, offer Florida a more humane, cost-effective, and evidence-based path forward. Prioritizing investment in affordable housing, wraparound services, and community integration aligns with both fiscal responsibility and long-term public health goals.

Comments